Table of Contents Show

1. Only around 3% of CEO compensation is linked to the achievement of climate-related targets at the largest US oil and gas companies.

2. The climate targets indicated in their compensation packages are typically weak or ambiguous.

3. Despite companies’ often bold-sounding declarations, boards are not meaningfully giving senior leaders incentive to align their strategies and performance with the energy transition.

4. Investors possess powerful tools to encourage companies to align C-suite executive compensation with the achievement of meaningful climate targets.

In theory, CEO performance targets should drive forward key elements of corporate strategy to deliver reliable returns. Under pressure from investors, carbon-intensive companies are rapidly adopting climate-linked incentive practices. Quantifiable greenhouse gas emissions reductions, goal posted against a net-zero-aligned pathway, are considered ideal metrics for calibrating incentive pay at companies most exposed to climate transition risk. And “say on pay,” which lets shareholders endorse or oppose such incentive practices, gives investors a voice on this topic where it matters the most.

Yet anyone looking at pay packages in the oil and gas industry would have to look hard for evidence that the companies are taking the carbon transition seriously. Instead, pay arrangements at large US oil and gas companies are more geared toward business as usual than transition objectives, according to Morningstar Sustainalytics’ 2024 proxy season research and voting recommendations. This highlights a clear disconnect between the interests of diversified investors aiming to decarbonize their portfolios and avoid climate-related losses, and those of oil and gas company CEOs with much shorter decision horizons.

As we’ll show later, we believe oil and gas companies’ CEO pay arrangements encourage a “business as usual for as long as possible” mindset with only a nod to their flashy energy transition aspirations. We’ll also show that investors can play a role in changing this by using the say-on-pay vote.

The Global Energy Transition Is a Governance Challenge for Oil and Gas Companies

As the energy transition accelerates, and the world approaches peak fossil fuel demand, oil and gas companies face a stark reality: Transform or risk obsolescence.

The International Energy Agency’s 2023 World Energy Outlook projects peak demand for coal, oil, and gas by 2030, driven by increasing investment in clean energy. More aggressive climate policies, consistent with the Announced Pledges or Net Zero by 2050 scenarios, could further hasten this decline.

These shifting dynamics are prompting increased scrutiny of climate transition plans—companies’ strategic blueprints for navigating the low carbon transition.

For best practices, transition plans should set out quantitative targets for emissions reductions. This means achieving operational carbon efficiency improvements, measured against scope 1 and 2 emissions reductions. But investors also expect carbon-intensive businesses to target scope 3 emissions: the greenhouse gases released upstream and downstream of the business.

For fossil fuel companies, with up to 95% of their carbon footprint in the coal, oil, and gas products they sell, a defendable transition plan might entail diversifying energy portfolios, developing carbon removal services, and supporting upstream partners’ decarbonization efforts.

Indeed, ambitions expressed by US oil and gas companies on their websites and in sustainability reports feel encouraging. EOG Resources EOG aims to “[play] a significant role in the long-term future of energy.” Phillips 66 PSX is working “to meet the world’s changing energy needs.” Valero Energy’s VLO vision is “advancing the future of energy.” EQT EQT is “[g]uided by the purpose of providing energy security to the world and lowering global emissions.” ExxonMobil XOM is “… helping accelerate society’s path to net zero by scaling up emission-reduction solutions,” and so on.

But investors know that the critical link between corporate ambition and corporate action is corporate governance: the rules and practices that enable management and the board to run the company effectively.

In recent years, carbon-intensive companies have introduced climate targets into compensation plans, specifically the “variable” part that is performance-based. This is where CEOs and senior executives must achieve emissions reductions and other climate strategy milestones to earn a specified portion of their performance-based pay. Companies are given credit for adopting this practice within several well-referenced climate action frameworks, such as the Climate Action 100+ Company Benchmark. Ideally, these incentives are quantifiable and use targets derived from companies’ transition strategies, which in turn map to the decarbonization pathways used by investors and investor networks.

Based on our proxy season analysis of climate transition plans and executive compensation reports, we find that lofty climate goals receive relatively little attention in CEO incentive pay arrangements at the 15 largest oil and gas companies in the US. For companies at the heart of the global energy transition, this should be a huge concern for investors.

Climate Transition Plans Fall Far Short of Paris Climate Goals, Starting With Corporate Strategy

Aligning CEO incentives with the global energy transition starts with corporate strategy. While all 15 companies we examined have published energy transition plans, some of which showcase investments in renewables, carbon capture, or low-carbon fuels, none have set credible net-zero or well below 2 degrees-aligned emission reduction targets.

Only five of the 15 companies have adopted targets on their material, or financially relevant, scope 3 emissions. Of these, three have targets for reducing absolute emissions. Occidental Petroleum OXY leads, having set a 2050 net-zero ambition covering the use of fossil fuel products. It has not set interim targets for incremental absolute reductions. Marathon Petroleum MPC sets a 2030 scope 3 reduction target but does not say what comes next.

Valero makes a modest, yet unconvincing, 2050 commitment to “reduce and displace” a specified volume of its emissions. These include scope 3 and even so-called scope 4 emissions (a new concept referring to emissions you help others to avoid), leaving open questions about how it plans to offset operational emissions with planned value chain emissions reductions. It is also one of three out of the 15 that has yet to begin reporting its scope 3 emissions.

Chevron CVX and Phillips 66 set interim targets for achieving scope 3 intensity reductions—reducing the amount of carbon emitted per unit of energy produced. Notwithstanding, both companies’ absolute emissions have risen year-on-year over the past three reporting periods. Across 10 companies that provided absolute scope 3 data for at least the past two reporting periods, scope 3 emissions have risen by an average of 4%, or more than 100 million tons of carbon. Morningstar Sustainalytics’ carbon emissions data shows that the 15 companies’ 2023 fossil fuel products amount to about 3 billion tons of carbon.

Climate Incentives Are Mostly Absent from Longer-Term Performance Evaluations

Our proxy analysis supports informed voting on pay practices at the heaviest emitters globally. It identifies and assesses the climate-linked portion of each CEO and senior executive pay plan within the overall composition of fixed and variable pay arrangements.

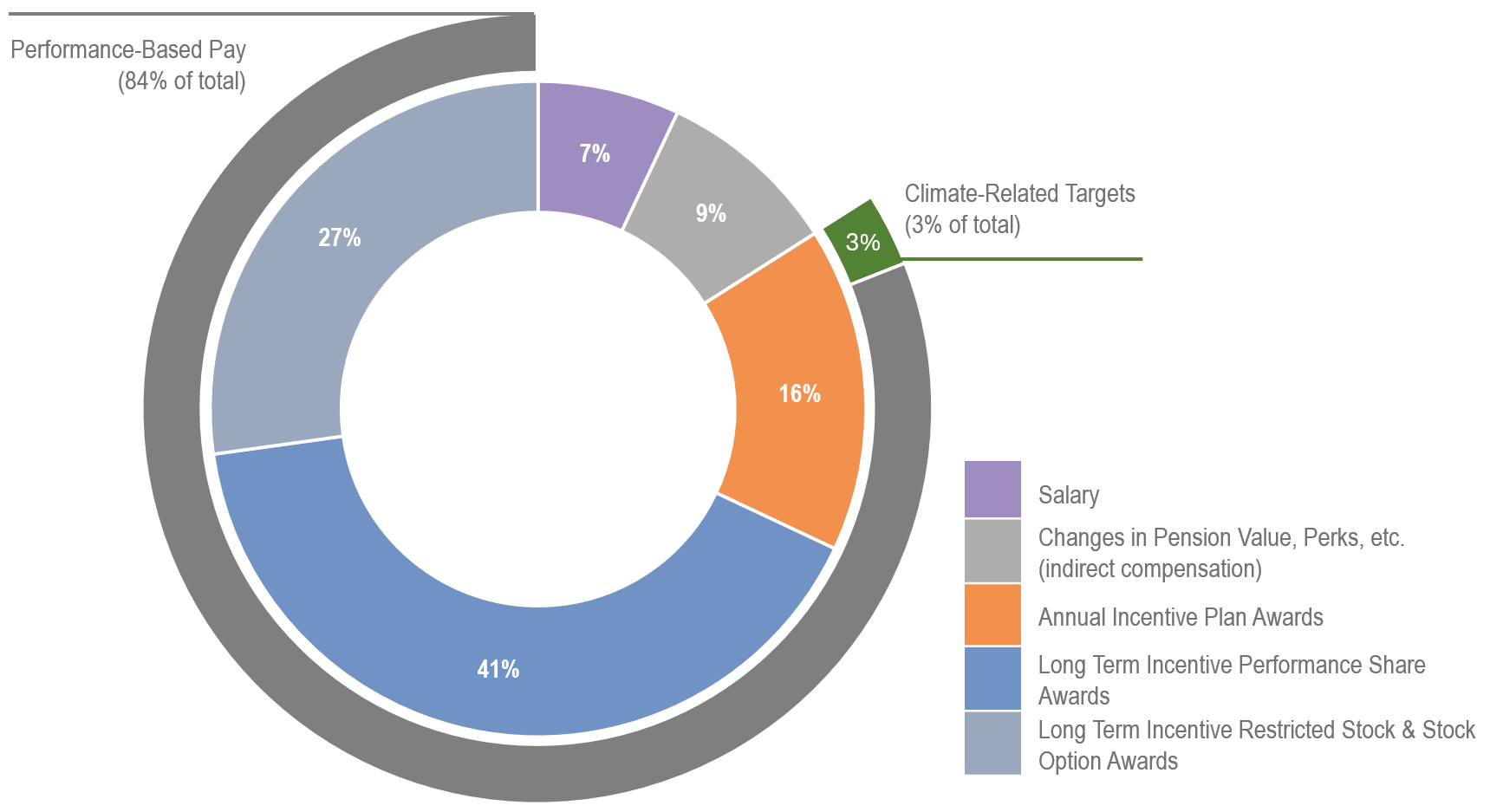

In 2023, variable performance-based pay accounted for 84% of the total CEO compensation, on average, across the 15 companies. Performance pay is generally derived from two types of plans: annual incentive plans and long-term incentive plans, which respectively accounted for an average 16% and 68% of CEOs’ total 2023 pay across the 15 companies.

Typically, LTIPs track performance over three years and offer payment in two share-based buckets: performance share units awarded for achievement of specified targets, and restricted stock units, which vest and accumulate value over a specified period.

The inclusion of energy transition progress metrics in LTIPs better aligns CEO fortunes with climate transition strategy time frames. Additionally, the absence of climate metrics in long-term incentives effectively erodes their influence over time. In the recent evolution of oil and gas company CEO pay structures, an increasing proportion of pay is contributed by long-term incentives, which grew by $2.3 million on average since 2021, compared with AIP awards, which have not grown.

Exhibit 1: LTIP Awards Increasingly Dominate Oil and Gas CEO Pay

We found that only Exxon Mobil and Valero factored climate considerations into their CEOs’ LTIP arrangements. In each case, the overall impact on final payouts is unclear. However, owing to the larger portion of pay from LTIP awards, we estimate climate targets to have had a somewhat stronger influence on CEO pay in both cases: 17.5% and 9%, respectively.

For 13 of the 15 companies, climate actions were represented only as annual performance metrics.

Climate-Linked CEO Targets Will Not Deliver Real-World Decarbonization

Based on companies’ compensation proxy disclosures, we estimate that, on average, a scant 3% of CEOs’ total 2023 compensation was determined by their performance against climate goals.

Exhibit 2: Typical Makeup of Oil and Gas CEO Pay in 2023

None of the 15 companies articulated explicit scope 3 emissions reductions as a CEO performance metric.

Climate targets were typically framed as intensity reductions on operational emissions or as targets to reduce flaring or upgrade equipment to prevent methane leaks. For example, Devon Energy DVN assigned its CEO the target of reducing the intensity of its scope 1 and 2 emissions and improving methane emission detection, together a 14% weighting within the company’s AIP, or around 1.4% of total pay.

While actionable and worthy as intermediate business challenges, these targets do not challenge CEOs to plan for new sources of revenue in a world of declining fossil fuel demand.

Furthermore, in all but one case, proxy statements report that CEOs exceeded climate targets. Targets that are too easily attainable deliver guaranteed payouts to CEOs.

Informed Investor Votes Should Veto Poorly-Designed Climate Incentives

While investors might be encouraged by the apparent uptake of climate incentive pay metrics in recent years, the combined $281 million awarded to the 15 CEOs in 2023 appears to have had little to do with the steps they took to advance resilient business models ahead of peak fossil fuel demand.

One way investors can drive better alignment is in how they vote to approve CEO and senior executive pay practices. The say-on-pay vote asks shareholders to approve a company’s approach to the compensation of top C-suite executives. Across the 15 companies, the average 2024 say-on-pay support was 92%, well above the average for the S&P 500.

Even if a vote doesn’t fail, low support can drive meaningful shareholder engagement. New SEC voting disclosures that came into effect for investment fiduciaries in August may raise the significance of the say-on-pay vote as a governance measure.

As CEO pay continues to rise along with oil and gas companies’ scope 3 emissions, investors should take climate transition alignment into account when casting votes to approve senior executive pay arrangements.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.